Labor Day in the Multiverse

Organized labor improved the health and health care of other countries. Would that be the case if the United States had a stronger labor movement?

Social scientists often attempt to understand the world as it exists by comparing it to a hypothetical alternative that doesn’t. This counterfactual approach to causation tries to establish that A causes B by considering, theoretically and empirically, whether the absence of A would also result in the absence of B. Although a useful method, this approach is limited in its scope for exploring complex and long-spanning hypotheticals.

Marvel may have a better, or at least more fun, approach. The latest offering from the comics-based studio is a show called What If, which retells its classic stories by imagining how a minor difference can lead to a cascading series of changes resulting in an entirely different universe. The stories take place in a multiverse with an infinite number of branching timelines, all with different narratives, battles, and outcomes from our own. Although the episodes tend to focus on superheros and villains, these branching timelines represent entire parallel worlds, presumably with their own health care systems and vigorous policy debates.

The history of U.S. health care is filled with a lot of “what ifs.” The repeated failure of universal health care legislation in the United States can create a false impression that it was never wanted or a real possibility, but there have been attempts to reform health care for more than a century, some of them close to passing. If a few minor events had transpired differently—a different election outcome here or there—we might have lost the outlier status as the only high-GDP country without universal health care long ago.

But there are also some deeper structural reasons for those outcomes. The United States is not just an outlier when it comes to health care delivery, but also a range of political, economic, and social characteristics that both shape and result from the development of its health care system. One of those is a relatively weak labor movement. Compared to its peers, the United States has historically had lower rates of union membership and a relatively weak overall labor movement that passed its heyday several decades ago. As I’ll explain below, there are many links between unions and both health and health care that make this an important factor in the broader story of U.S. health care. Both population health and health care in the United States might look entirely different in a counterfactual universe with more labor unions, which begs the question….

What if the United States had a stronger labor movement?

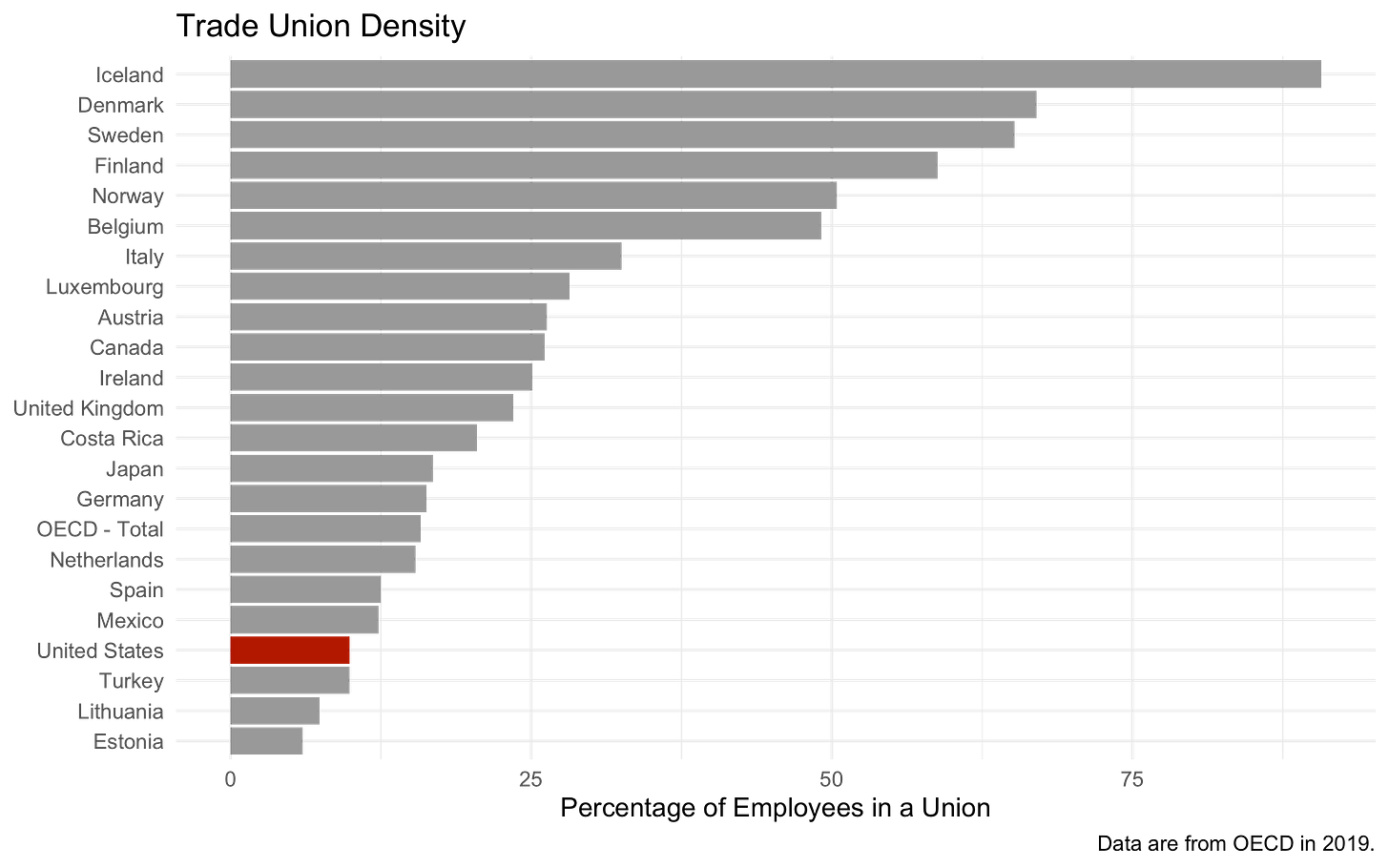

An alternate universe with a stronger labor movement would look different in a couple of ways. First is union membership. The United States has a lower rate of union membership than most high-GDP countries—only around 10% according to the OECD data in the figure above. Compare that to over 90% in Iceland or more than 60% in most of the Scandanavian countries. Union membership rates were higher in the early and middle part of the 20th century, but even at peak levels of union membership, the United States has been a bit of an historical outlier.

More unions would obviously make a difference for the workers in those unions. Union jobs consistently have higher wages than non-union jobs. They have better health insurance and access to health care. They have better retirement funds, more sick days, and generally better benefits overall. Union workers in this alternative timeline would likely be healthier both because of their improved access to health care but also due to the variety of health benefits associated with higher wages and a better work environment.

But there would also be an aggregate difference between the timelines. An individual in a union will have a different employment experience than their variant in a non-union job, but it’s also the case that a society with higher levels of union membership will be a fundamentally different society. Social scientists aren’t just interested in the individual labor-capital relationship, but how the organization of labor and movements of laborers can re-align the power balance in societies.

In fact, some scholars have put organized labor as a central driver in the development of the welfare state in capitalist democracies. This “power resources” theory is interested in how the mobilization of resources in markets and politics shapes the struggle between classes and their relative success in influencing societal institutions. Although private capital has the money and influence to dominate when unchecked, workers have greater numbers and can push the state toward more egalitarian policy when successfully organized. A strong labor movement is like an assembled Avengers team, capable of winning victories against the overpowered billionaire mad titans of industry.

Some of the countries with the strongest labor movements in early-to-middle 20th century were able to successfully push for an expanded welfare state with a broad social safety net and redistributive policies that included universal health insurance or health care. In many cases, labor movements coalesced into distinct political parties and worked directly within the political system. While the labor movement in the United States has been involved in pushes for welfare state expansion, particularly during the New Deal era, it fell short of the universal achievements seen in countries where labor wielded more power via its strength in numbers.

U.S. health care in the multiverse

So if the United States had a stronger labor movement, it’s possible that could have shifted the balance of power resources and led one of those previous pushes for universal health care to be successful. But which one? The problem with the “what if” game is that only changing one aspect of the timeline leaves other, more important barriers, still in place. Proponents of universal health care weren’t only up against the interests of capitalists in the early post-war attempts to expand access, but faced a bigger villain in the form of white supremacy and Jim Crow segregation.

An alternative to a standalone power resources explanation for failed health care reform in the United States includes an understanding of how racism has shaped every aspect of life in the U.S., particularly during the period of welfare state expansion following World War II. Politics around universal health care hinge on more abstract questions of collective identity and belonging. Many countries during this period decided that every citizen had a right to the some baseline of health care, regardless of their differences. Reaching a similar point in the United States would have required white politicians and voters to willingly share health care resources and risk pools with black Americans who they did not consider their equals.

The collision of welfare state expansion and white supremacy left an imprint all across the New Deal. When Social Security Insurance were created, segregationist politicians pushed for provisions to exclude agriculture and service occupations that were dominated by black workers, effectively creating a mostly-white program for the first years. Benefits of the GI Bill were similarly racialized. Redlining practices effectively excluded non-white Americans from federal housing subsidies, and segregated universities helped funnel education assistance to white veterans.

It’s hard to see universal health care making it through the New Deal, even with a strong labor movement as its advocate. Perhaps a more likely timeline is one in which organized labor joined the aims of the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s to simultaneously push for universal health care. As David Barton Smith argues in The Power to Heal, it is no coincidence that Medicare and Medicaid passed right after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as the push for health care was inextricable from the broader civil rights struggle given the separate and unequal hospital system that existed under Jim Crow:

The notion of “social solidarity,” invoked in other countries, never came up as an argument for universal protections in the United States. Only during the civil rights convulsions of the 1960s did the notion of “being all in it together” have any salience. Medicare, in its essence, was a gift of the civil rights struggle.

Maybe there’s a timeline where that push doesn’t have to settle for piecemeal programs of Medicare and Medicaid, but leverages the two movements to successfully push for a universal system.

Population health in the multiverse

The more substantial butterfly effect of a strong labor movement might show up in the factors that shape population health outside of the health care system. The power resources literature doesn’t focus exclusively on health care, but instead examines how a society with a large movement of organized labor shapes a range of policies tied to the welfare state.

This includes everything from minimum wage laws to general approaches to taxation and redistribution. Many of the statistics showing the United States as an outlier are just different manifestations of its overarching outlier status as a place where wage laborers have lost leverage in the political system, resulting in variations of policies favoring corporate and wealthy interests. The countries with the most robust welfare states in the world also have some of the best aggregate indicators of population health (i.e., long life expectancy and low infant mortality), even though they have not eliminated relative health inequalities, particularly along socioeconomic lines.

Maybe in a timeline with well-organized labor, some of the neoliberal policy shift that preceded the decades-long stagnation in life expectancy in the United States never fully happens. It’s no coincidence that Ronald Reagan kicked off his term with a confrontation with a union, firing 11,000 air traffic controllers in a real and symbolic defeat to organized labor. In a world with a broader labor movement, that battle might turn out differently.

Labor and health care today

The premise gets a little more complicated if the timeline makes it to present day before diverging. Despite the historical evidence for power resources mobilization and the strong labor union support for health care reform in previous eras, the health care politics of today’s unions is hard to decipher.

Just this week a team-up of labor unions and the pharmaceutical industry began airing ads attacking a plan that would allow the government to negotiate lower drug prices. This defense of private pharma interests appears to be some kind of quid pro quo in return for the pharmaceutical industry’s use of union labor to maintain its research and production facilities.

Today’s labor movement is also divided when it comes to Medicare for All and other contemporary plans to reform health care. While some unions still maintain the traditional labor stance of pushing for universal coverage, others are opposed to disruptions to the status quo, in part because unions enjoy a comparative advantage in the private health care marketplace. Unions are able to pool risk and collectively bargain for better health insurance plans than workers can access in many non-union jobs, and some union leaders appear reluctant to ditch a system that creates an incentive for union membership.

Again, there are differences between being a member of a union in a society with few unions versus many. It’s possible that this comparative advantage would be less of a factor in a timeline with a broader labor movement that didn’t need to compete as hard for membership and had the power to enact broader worker-friendly policies. Or maybe labor’s heel turn on health care policy is another piece of evidence, growing since around 2016, that we are already living in some kind of bizarro alternate timeline.